The Intentional Organisation - Issue #46 - What happens when we don't design intentionally?

In the tension between consistency and congruence, what is the impact of unexpected consequences of emergent design patterns? If we are not intentional, how do we avoid value destruction?

1. Missing Intentionality in Design

In the last issue of this Newsletter, I wrote about Consistency and Congruence, which are also associated with the dualism of Intentionality and Emergence in Organisational Design components.

I received a question on the impacts of not intentionally designing one (or more) of the components listed in the Organisation Evolution Framework. I have been thinking about it for a few days, and today, I will share my initial views on what happens in reality.

“un-intentional” design: what happens?

The above chart shows a hypothesis based on a particular situation that one of the elements is not designed intentionally (thus, it is missing the “congruence” link with the rest of the components). In this Newsletter, I will analyse the first four components of the Organisation Evolution Framework (Business Model, Strategy, Operating Model, and Organisation Model), leaving the other four to the next issue.

First, two general warnings:

All these cases are purely theoretical: it is difficult to see a situation where only one component is not designed “intentionally”. When this happens, the component will develop as an emergent attribute of the organisation (remember, all these components are always present).

Congruence is a dynamic process: organisation components that are designed intentionally tend to age in line with the mutation of the context. So it can happen that an element that was designed intentionally is not anymore “fit” to the situation.

So let’s see four specific cases.

1. Undefined Business Model: The Me-Too Organisation

What happens when we don’t intentionally design a Business Model for our organisation?

This means there is no formal definition of our value proposition and no conscious identification (at minimum) of our customers or consumers.

The organisation accepts a “me-too” approach, copying similar organisations already on the market or delegating the definition of its Value Proposition to other elements of its design.

👉 Consequences: This causes the formation of an Emergent Business Model where some of the critical attributes might not necessarily be under the organisation's control. A few cases can appear:

Unclear route to market: A start-up company could focus so much on their innovation strategy (focusing on R&D), only to realize that the products created do not have a straightforward market application, as the organisation failed to identify potential customers.

Issues in identifying market constraints: A group of employees from an existing company could create a “spin-off”, focusing their initial attention on operating and organisational model improvements compared to their previous employer, assuming they would compete in the same market and customer base. However, they might later realize that the former employer has created a barrier for them to access its customers, thus creating issues in their route to market.

Missing proposition for their customers: A non-profit organisation could be created with a strong focus on a prominent and ambitious purpose. Still, it could fail to identify potential donors, thus vanishing their initial efforts.

2. Undefined Strategy: The Directionless Organisation

What happens when we don’t intentionally design a Strategy for our organisation?

Many would argue that finding a company without a strategy is almost impossible. The reality is that many organisations don’t have a real strategy but rather a liturgy of processes that project their financial results in the future. The biggest mistake many make is assuming that a budget is a strategy. Wrong. There is a lot more than cost and revenue definitions into strategy definitions. Thus, the possibility that the Strategy is not designed intentionally is pretty high.

This means there is no formal definition of our Strategic Choices, which means not having clear priorities in the organisation.-

The organisation accepts a “Directionless Status,” whereby direction (or criteria) are not formalised; thus, choices are made tactically. There might be moments when being tactical can be a strategic choice, and there might also be moments when an opportunistic approach might be the best way to capture opportunities.

After all, Henry Mintzberg directly theorised the formation of an Emergent Strategy in his Strategy Safari as one of the possible (and valuable) alternatives to an intentional plan.

👉 Consequences: the absence of a formal intentional strategy can create issues sometimes, for example, when:

Inconsistency in product portfolio: A company that is very active in M&A could develop a purely opportunistic approach, buying what is available on the market and ending up with a portfolio of inconsistent products or services.

Incapacity to define value: A start-up that is very active in R&D could start developing a product, then continue to move in a direction in terms of prioritisation of components and results, ending in a vicious circle that doesn’t allow the company to capture value.

Missing alignment of goals and activities: An organisation might fail to update its strategy after a disruption in the market, causing employees and managers not to understand new prioritization within the organisation. This can create hectic behaviours and erratic results.

3. Undefined Operating Model: The Random Organisation

What happens when we don’t intentionally design an Operating Model for our organisation?

In my experience, this is the most frequent case. Too many organisations focus on drawing org charts and internal policies but fail to stand before their drawing board and actively build their operating model. To me, this is akin to planning a house by focusing solely on the interior design without a clear focus on designing its structure, including the wiring and plumbing.

This means there is not a shared understanding of the Value Delivery Chain of the organisation.

There’s a shared assumption that by simply adopting a traditional organisational model (let’s say a functional hierarchy) and having a definition of our Business Model and Strategy, the rest will follow. In my experience, this assumption can work only in simple markets with no differentiating skills and limited innovation. In how many cases does this happen?

The problem with not intentionally designing your operating model is that many choices will create inconsistencies within the organisation without you expecting this.

👉 Consequences: the absence of a formal operating model will create issues in the form of:

Bloated Systems and Technology: A company implementing a new ERP tool will often approach the implementation purely from a technology perspective, failing to tune processes to its internal requirements and finding itself with bloated systems that are not always fit for purpose.

Unfit Structures: A new company that starts operations without a clear Operating Model in mind could find itself with way too big back-office operations compared to its front office, resulting in productivity issues that could lead to bankruptcy.

Siloed Mentality: A company that implements a functional organisation without clarifying the other components of its operating model will quickly develop a siloed mentality and will have challenges connecting value-creating processes.

4. Undefined Organisation Model: The Chaotic Organisation

What happens when we don’t intentionally design an Organisation Model for our organisation?

This might seem remote, but many organisations fail in the initial steps of their development journey because they don’t plan their organisation model coherently. I see two prominent cases here: 1) companies that assume that a hierarchical organisation is a way to go without giving a thought to the actual needs of their business and 2) organisations that decide to explore alternative organisation models but don’t spend enough time in assessing if it fits their needs.

The first case is way too typical, often intercepting a missed focus on the operating model. We assume we need a functional/hierarchical organisation and let it grow based on the requests of individual managers. This can quickly produce an unsustainable outlook.

Unfortunately, the second case is also becoming more frequent and is one of the main reasons some self-management experiments fail. The organisation does not spend enough time assessing the best model for them, the rules of the game and the ways of working.

This means there is no shared understanding of the definition of work for the organisation.

👉 Consequences: the absence of an intentional organisation model will create issues in the form of:

Unsustainable organisation sizing: where structures are created more to balance internal power structures than real business needs.

Unclear governance: the organisation will have difficulties prioritising activities and goals, allocating resources, and ultimately choosing its own path to success.

Low engagement levels: The organisation will fight to define a value proposition for its employees and collaborators regarding how they contribute to its success.

An Initial Conclusion: The role of intentionality

We have seen above a few examples of how not applying intentionality to the design of each of the organisation's design elements can create problems in both consistency and congruence of the system. In the next issue of this newsletter, we will cover the other four elements of the Organisation Evolution Framework (Leadership, Culture, Purpose and Ecosystem). Still, it is already possible to establish a few conclusions:

Yes, we can allow some elements of design to emerge in time. Still, it is critical to ensure we monitor each component's impact on our system's overall sustainability. We need to be able to assess the unintentional consequences of missing decisions.

Intentionality means capturing the interconnectedness of the various components. This ultimately means that we don’t have to design each element to the maximum level of detail but to the level that is “good enough” to ensure the required level of congruence.

Copying from others (also in the sophisticated form of benchmarking) is often the best way to create problems. Why? Because most of the components are not neutral to the situation in which we cascade them. This is why even the simple implementation of a system with a standardised process defined elsewhere can cause issues if it is not framed in an environment of intentionally defined boundaries, rules of engagement, and so on.

What do you think?

— Sergio

2. Site Updates

The Laws of Organization Design

I have continued publishing my articles on The Laws of Organization Design. Here is the complete list of articles published:

The Laws of Organisation Design

Conway’s Law and Intentional Design (reviewed article)

More to come in the coming weeks!

— Sergio

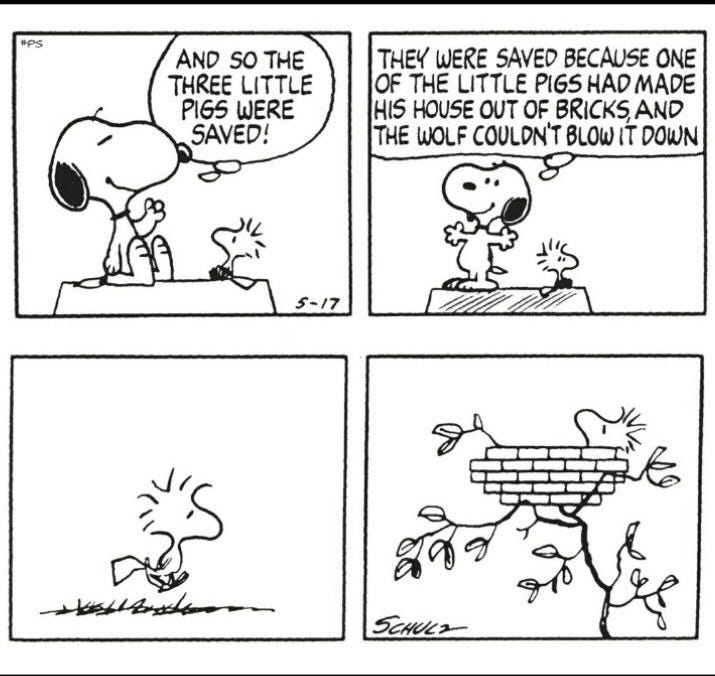

3. The (un) Intentional Organisation 😁

Source: Pinterest

4. Keeping in Touch

Don’t hesitate to reach out by directly hitting “reply” to this newsletter or using my blog’s contact form.

I welcome any feedback on this newsletter and the content of my articles.

Find me also on: